Before the premiere of Turandot

Agnieszka Drotkiewicz talks to Karolina Sofulak about the power of opera and a metaphorical trip to Mars – right before Kraków Opera’s latest premiere.

Giacomo Puccini Turandot

premiera: 25 March 2022, Kraków Opera

Agnieszka Drotkiewicz: You are a highly versatile director – you recently produced Verdi’s Masked Ball at the Danish Royal Opera in Copenhagen, and you’re now working on Puccini’s Turandot at the Kraków Opera and reprising Eötvös’s The Golden Dragon for the Opera Rara Festival [held between 12 and 28 February – ed.]. How would you describe the difference between working at major, historic institutions and festivals?

Karolina Sofulak: It’s true that I am a travelling director, and I have worked at a range of institutions in many countries. My experience has shown me that the convention of each spectacle should be determined by the audience – before we even start working on a project, we should consider how we want to tell the story. That’s how we decide on the format. We have different audiences attending operas and festivals, and the way we work on the shows is different. At theatres, the work is longer term: the opera enters the repertoire and it is performed regularly. Meanwhile, at festivals we follow the stagione approach (similar to seasons), where plays are performed just a few times.

How does this affect the repertoire?

Most opera theatres in Poland stage the best-known plays – a selection of around twenty including La Traviata, Carmen and Madame Butterfly. The canon focuses on the late 19th and early 20th centuries (Verdi, Puccini), sometimes bel canto and Mozart, rarely something earlier (Monteverdi) or later, post-Britten. Less well-known operas tend to be shown at festivals, where the style of work is more suitable. Opera Rara is doubtless the most ambitious event of its kind in Poland. Each instalment of the festival includes titles which explore contemporary issues and expand our sensitivities. I’d like to add that I’m not talking about a simple juxtaposition of escapism vs. popularity – the wonderful thing about art is that when it talks about current issues it touches on universal values.

You need to constantly work on your own knowledge and sensitivity to find operas which will broaden the audience’s mind

That’s right – working in opera means we are constantly learning and perfecting our craft to be able to share what we've discovered. It also helps us to step beyond the twenty obvious titles to provide fresh experiences for our audiences. Paradoxically, many titles in the operatic repertoire remain unknown precisely because they are unknown – no-one wants to dust them off and rediscover them. That’s why festivals are so important – Kraków’s Opera Rara provides a space for experts to share their passion and knowledge.

When you’re working at a major venue such as the opera house in Copenhagen, you have access to a large support team, extensive workshops and full infrastructure. At other times, you have barely any budget or team. How do you cope with such major changes?

All situations when you have to think beyond financial or production frameworks free creativity; for me they are moments of artistic stimulation and times to really practice my craft. When you’re faced with limitations, you have to rely more heavily on your craft because you don’t have elements of expensive productions such as opulent settings and hundreds of people working to create the WOW effect. Working in more restricted conditions makes me feel even more strongly that opera is something bordering on a miracle.

When I try to compare the operatic classic Carmen with The Golden Dragon – a work dealing with the topic of immigration – I think about the music. Both Habanera (Carmen’s aria L’amour est un oiseau rebelle) and the moving lament of the protagonist of Eötvös’s opera convey deep emotions…

…that’s right, you feel this music in your body – we experience it on a somatic level with the actors. A good production creates tension and its release on many levels including erotic, and this affects the viewer’s senses. We immerse ourselves in this world, and a kiss between the protagonists may feel like our very own… The power of opera lies in the fact that it happens live, like theatre, and relies on music, like cinema. In any case when operas were originally being written, they were almost like Hollywood – imagine the Tarantino of the Baroque!

You and the stage designer Ilona Binarsch started working on your interpretation of Turandot for the Kraków Opera by studying the legend of the protagonist. Tell us about what you learned.

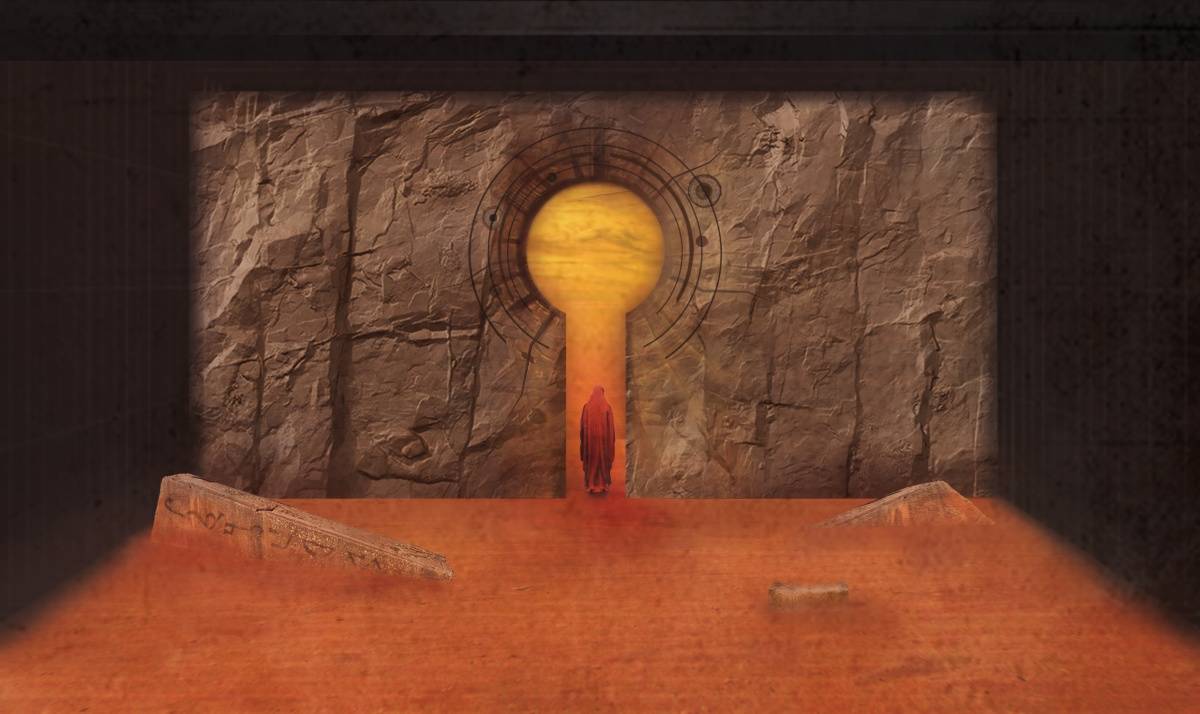

Turandot is one of the operatic standards I mentioned earlier. It’s set in China, and I think that staging this orientalist piece without reflection would mean that we would be following blasé colonial discourse. When Ilona and I did some proper research, we discovered that it isn’t even a Chinese tale! Princess Turandot was first described by the Persian poet Nizami at the turn of the 13th century in his epic poem Seven Portraits. Each instalment tells the story of each of the king’s seven brides; each comes from a different part of the world and lives in a palace of a different colour, overseen by a planet governing the day of the week when she is visited by the king. Turandot comes from the land of Saqaliba – our own Slavic region! She lives in a red palace, her planet is Mars and the king visits her on Tuesdays. This means the story is told by the sophisticated culture of the east about someone who – from the poet’s perspective – comes from the Wild West. This has been one of the inspirations of our interpretation.

You turn the map around and show something seemingly obvious: that East and West are completely subjective concepts.

That’s right – we are reaching for the original version of the story. The Chinese element first appeared in Carlo Gozzi’s 18th-century version of Turandot tale which was one of Puccini’s inspirations. Our version doesn’t mention China; in fact we set the story on metaphorical Mars, that is Turandot’s planet from Nizami’s epic poem, and we flirt with sci-fi. This is important, because we don’t change the opera’s dynamics even though we move the setting. Operas with important social elements tend to lose out when they’re transposed into a purely abstract world of internal experience. Turandot is just such an opera – it is set in a royal court, it’s spectacular, and the status of the protagonists is important. It is an archetypal fairytale, told in a folk language which can be understood beyond borders and time and in different contexts.

Kraków is an important city on your personal map: you studied direction of opera and music theatre here under Prof. Józef Opalski, and he is supervising your PhD…

…which is about Dvořák’s Vanda – the first opera I directed at the Opera Rara Festival.

You’d struggle to find a more Cracovian opera than Vanda!

That’s right! I think it should be a permanent fixture of Kraków’s repertoire, because it is a beautiful telling of the story of Queen Wanda. And yet it’s hardly ever shown! Why? Because it was written by a hugely talented but inexperienced composer, and his grand opera features five acts, a vast choir and solo roles for Wagnerian voices, almost impossible to find in Poland. Before we could stage it we had to cut it, adapt it and work on the score.

Like editing?

Exactly! The literary comparison is very apt here, because musicology is yet to have the debate on the death of the author which has been widely explored in literary studies. It’s something much needed, and it will be the subject of my PhD: creative acoustics, choir divisions and fresh adaptations which will help us resurrect and revive many unfairly forgotten works. It’s far better to perform an adapted, edited opera – to taste it and pay homage to the composer – than to just abandon it.

With all your experience, why do you need a PhD?

To help young singers. I spent many years working abroad, mainly in England, where I gained so much practical experience which simply can’t be taught at university. I would like to share what I learned from my teachers with our future singing stars. I see it as my duty to engage young people and encourage them to sing on Polish stages, and I hope we can work together in the future!

- Karolina Sofulak

A director who debuted at Opera North – one of the most progressive operatic institutions in the UK. She was the first Pole to win the European Opera-directing Prize (EOP) for young opera directors in Zurich. She works in Poland and Europe. In December 2021, she produced an acclaimed adaptation of Verdi’s Masked Ball at the Danish Royal Opera in Copenhagen.

Photo by Klaudyna Schubert

- Agnieszka Drotkiewicz

Author of novels, interviews, essays and collections of discussions on topics such as art, literature, social issues, music and cookery. Jointly with Ewa Kuryluk, winner of the Warsaw Literary Premiere. She works with the “Przekrój” and “Kukbuk” quarterlies, and she has been published in “Wysokie Obcasy”, “Ruch Muzyczny” and dwutygodnik.com.

Photo by Antonina Samecka Risk made in Warsaw

Interview from the 1/2022 issue of the "Kraków Culture" quarterly