Artists who broke social taboos, women trying to smash the system and eccentric art collectors were the talk of Kraków at the turn of the 20th century.

The dark, twisting streets of Kraków were slowly being invaded by bitter-sweet artistic trends drifting in from the Old Continent. There was talk of humankind’s fragility, decadence, weakness and passing; women were increasing fighting for their rights. Opinion-shaping debates were shifting from upper-class salons to pubs and coffee shops filled with bohemian artists, marking the atmosphere in the city like a barometer. But who really were the people who had such an impact on Kraków at the time?

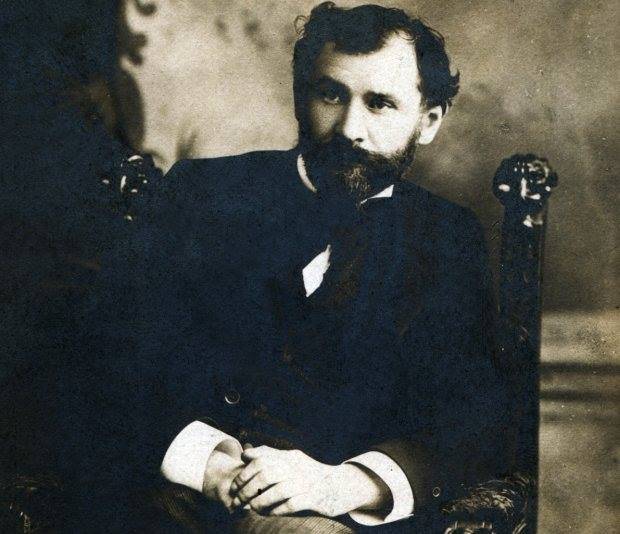

Bohemian provocateur

In the autumn of 1898, Stanisław Przybyszewski – renowned author, alcoholic and misogynist – stepped off the train from Berlin into Kraków. The city’s artistic circles welcomed him with open arms, and he was quickly surrounded by disciples fascinated by his radical views and extravagant lifestyle. Przybyszewski moved into a corner house at 53 Karmelicka Street, where he immediately started receiving admiring artists and even Satanists.

Soon after arriving in Kraków, he became editor of the magazine “Życie”, where he published articles postulating Modernism in Polish literature. His manifesto Confiteor is regarded as one of the most important texts of the Young Poland period. His motto was “art for art”, encapsulating his belief that artists were superior to ordinary people, and perhaps even held divine powers.

As well as his writings, Przybyszewski was infamous for being involved in myriad scandals. While living in Kraków, he started an affair with Jadwiga, wife of his friend Jan Kasprowicz, and maintained his relationship with the artist Aniela Pająkówna, even though when he arrived he was accompanied by his wife, the Norwegian pianist Dagny Juel – who, by the way, soon abandoned him and left Kraków with another poet. His domestic affairs were the talk of Galicia in the final years of the 19th century.

As befits a decadent eccentric, Przybyszewski was drawn to all things concerning death. His obsession was so powerful, in fact, that he took in his dying uncle, and certainly not out of compassion. He was desperate to get close to the world of the dead; in fact he was so excited by the prospect of his uncle’s death, he kept chanting, “Oh, how marvellous is the consumptive one in his final stages!”

Przybyszewski left Kraków for Warsaw in 1901, leaving myriad artistic ideas and domestic scandals in his wake. Although he spent just two years in Kraków, he made a major impact on Kraków’s bohemian scene and marked a distinction between artists and bourgeois society. He also injected a spirit of individualism into Polish literature, previously dominated by collective thought.

Emancipated atheist

Until the late 19th century, women were almost entirely absent from the public sphere, and their perceived role was limited to taking care of the home. One of the first Cracovian suffragists to express her disaffection was the poet, dramatist and social activist Marcelina Kulikowska.

She moved to Kraków in 1899 after graduating from natural sciences in Geneva. This was unusual in itself, as she was one of just a handful of women able to study abroad. She took on a job as a teacher at one of Kraków’s girls’ schools, but her career came to an abrupt end with a scandal with resounded throughout Galicia. One day, Kulikowska refused to attend church with her students, stating that she was an atheist and that this would conflict with her core beliefs. And if that weren’t enough, she came out in support of the still-controversial theory of evolution. This caused enough of a stir to be covered by the local press: “This same lady was instructing her pupils about the latest discovery of natural sciences: that man is just an ordinary animal!”

Her atheism was widely discussed for a long time, while Kulikowska herself remained steadfast in her principles; in any case her beliefs were highly personal, and she harboured no intentions of converting her students or challenging religious practices at schools. Still, her nonconformist attitude meant she frequently clashed with conservative circles and she was unable to continue working in education.

Critics largely distanced themselves from Kulikowska’s writings, although readers remained moderately interested. The author frequently expressed her frustration over her own fate and, more broadly, over the place of women in society. She couldn’t fathom why talented women weren’t better known, or why women weren’t given equal opportunities at education.

These frustrations and disappointments contributed to her poor mental health; sadly, on 19 June 1910 Kulikowska took her own life with a shot to the heart at her home at Pijarska Street.

Eccentric collector

Collector, aesthete, oddball, art critic and promotor, pianist… Feliks “Manggha” Jasieński was a colourful figure in Kraków’s artistic circles at the turn of the 20th century. During his travels to Europe and the Middle East, he amassed a unique art collection, which was the crowning achievement of his life’s work. Jasieński first arrived in Kraków in 1902, when he moved into an apartment at 1 Św. Jana Street. His home became a hub for Cracovian society – he hosted artistic events where participants discussed art, music and literature. In fact he received so many visitors, he hung a large cardboard cutout of a hand by his front door. Guests shook it in lieu of a personal greeting from the exhausted host…

Jasieński frequently used morally-dubious practices to obtain artworks. He was on friendly terms with many Cracovian artists and frequently visited their studios, where he would wait for the host’s moment of inattention, grab the piece he’d got his eye on, cut the conversation short and run off home with his loot. Still, Cracovian circles were so enchanted by him, his methods were soon seen as brilliant! The fact that an artist’s work was purloined by such a celebrated collector was seen as a compliment and evidence of their artistic worth.

Jasieński was perhaps best known for his fascination with Japanese art. His nickname “Manggha” originated from the series of woodcuts by Katsushika Hokusai. In spite of his extensive travels, he never made it to Japan, and the land forever remained almost mythical to him. The fascination is reflected in his collection, featuring around 6,500 artworks from the Far East. In 1920, Jasieński donated his collection of over 15,000 works to the National Museum in Kraków. In 1994, the Manggha Museum of Japanese Art and Technology, presenting Jasieński’s collection, was opened on the initiative of Andrzej Wajda.

***

Traces of activities of Przybyszewski, Kulikowska and Jasieński – echoes of bohemian spirit, a struggle for equality and extensive art collections – are still present in today’s Kraków. And these artists were just a handful of fascinating individuals who helped shape the city at the time. Who could forget the feminist Kazimiera Bujwidowa, architect Teodor Talowski (sometimes known as “Galicia’s Gaudi”) and the maverick doctor, author and inspired translator Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński… So many inspirational individuals! (Wojtek Zając, „Karnet” magazine)