We think we know Kraków and its monuments inside out, but perhaps some details are hiding in plain sight..?

During renovation works on the altar at the Basilica in 1867, restorers found a child’s shoe in faded yellow; half a century later, this discovery was described in a popular novel telling the story of the favourite apprentice of Master Stoss, the creation of the altar and mediaeval Kraków. Perhaps current renovation works on the Gothic structure, ongoing since 2015, will prove to be be memorable due to another important “discovery”? The organisers of the National Museum exhibition The Miracle of Light. Mediaeval Stained-Glass Windows in Poland are taking the opportunity to reveal the 14th-century windows in the presbytery, partially concealed by the monumental pentaptych. They are usually overshadowed by Veitt Stoss’s magnificent altar structure, even though the 115 original mediaeval stained-glass windows at the Basilica of St. Mary form the largest such collection in Poland; they are also some of the very few to survive at their original location throughout centuries.

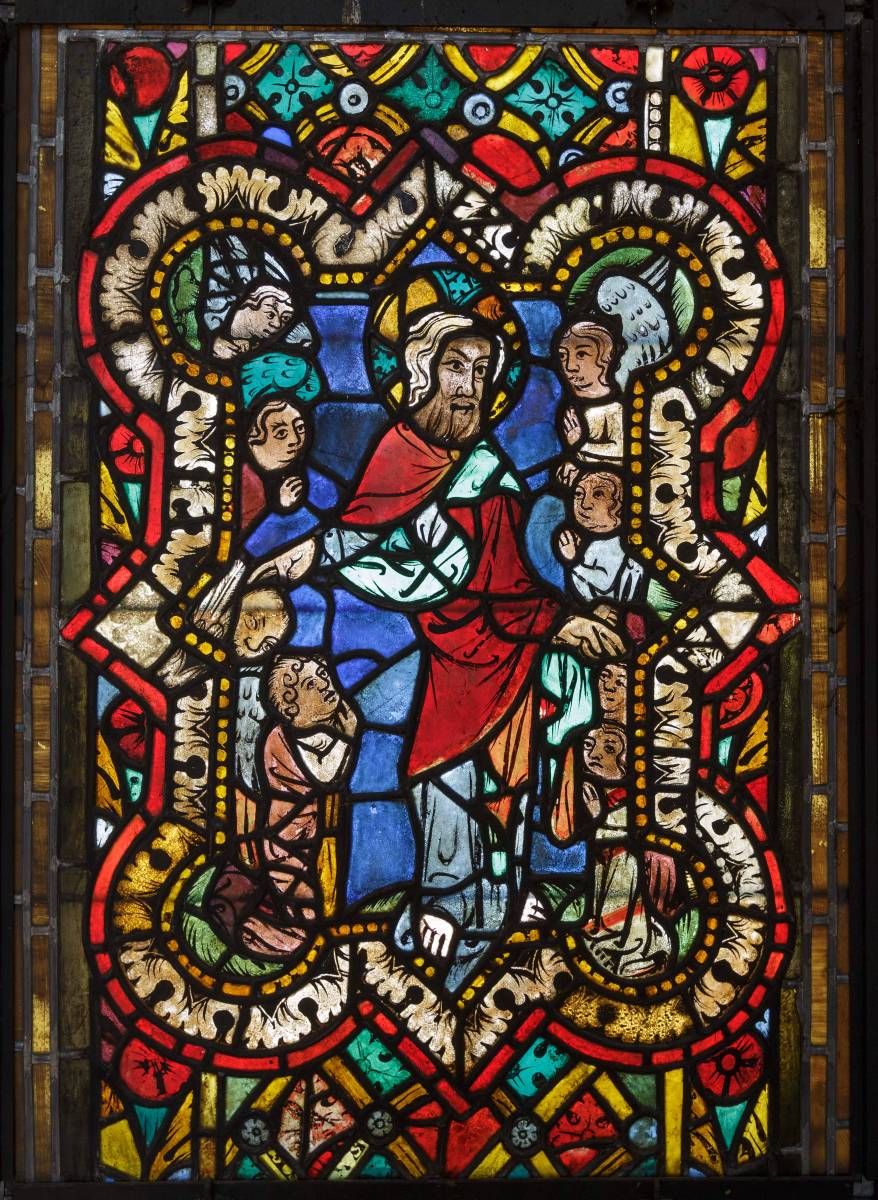

The monumental cycle, partly based on the Biblia pauperum manuscript, was made between 1360 and 1365, commissioned by the founders of the presbytery – Cracovians patricians and burghers, led by the famous Mikołaj Wierzynek. The work involved two independent workshops led by masters of the trade from Prague and Vienna, and their efficiency is as impressive today as it was over six hundred years ago. The craftspeople working on the current renovation were able to use their scaffolding to temporarily remove some of the windows in the apse (including The Creation of the Angels, The Creation of the Sun and the Moon, Drunkenness of Noah and The Crowning with Thorns). Fr. Dr. Dariusz Raś, archpriest and rector of the Basilica, released the stained-glass windows to make them the central point of the exhibition showcasing unique treasures of Poland’s churches, monasteries and private and public collections, launched at the Main Building of the National Museum in Kraków in February. The exhibition and its accompanying catalogue are the conclusion of the five-year project “Corpus of Mediaeval Stained-Glass Windows in Poland”, curated by Dr. Dobrosława Horzela.

Constructions of meticulously cut glass, coated with several layers of paint, fixed in a furnace and held in lead frames providing the contours, were working in Western Europe as early as the Carolingian period (9th century). As the Gothic style in architecture became more popular, it drove the development of stained-glass windows. Vast openings in soaring walls were perfect for filling with increasingly intricate glass. Dazzling compositions in church windows came to life at sunrise to praise the Lord the Creator and tell the story of the creation of humankind, with images of saints reminding the faithful of their moral duties. Although the complex theological context was generally only understood by highly educated elites, the dazzling light and colours were admired by all. Stained-glass making soon became one of the most important artistic field of the Middle Ages.

Creating architectural coloured glass was a vast artistic and technical challenge: it required expert knowledge, precision and in-depth understanding of architectural concepts. It was also extremely costly, so successful constructions served as validation of their patrons. So how did mediaeval stained-glass makers work? What skills were required to create their illuminated images? The process would start at a workshop from preparing a general design layout known as vidimus [Lat. “we have seen”]. After the plan was accepted by the patron, the constructors had to obtain the necessary materials. Sometimes they had to be imported from distant parts of Europe, but the effort was worth it, since the precise selection of materials affected the final colours and quality and quantity of light. The most important point driving the success of the entire project was creating a precise sketch of individual windows on a 1:1 scale to make sure the pattern fitted the space it was intended for. This task was reserved for the master craftsman, who was handsomely rewarded for his duties. In the 14th century, designs were drafted directly onto specially anchored wooden table tops (and let’s not forget that Poland’s first paper mill wasn’t founded until 1491!). Craftsmen selected the right glass for each window, which was then cut using a hot metal rod and formed to the right shape using specially-designed tongs. Colour was achieved using pigment such as powdered copper or iron with added wine or urine, and the timbre was obtained by applying a thin layer of patina. The tinted side was placed on the inside of the building so that it wouldn’t be damaged by rain or frost. Once the individual glass pieces were ready, they were arranged on the table and joined into a single whole with bars cast from lead and tin. The final stage of fitting the windows required expensive scaffolding, and was carried out in close collaboration with stonemasons cutting the tracery and other construction workers. It was only at this final stage when any errors came to light…

All this in mind, it is no wonder that stained-glass makers were held in high esteem and their works were regarded on a similar level as those of sculptors and painters, especially during the late Middle Ages. These craftsmen congregated in trade guilds, and stained-glass makers were frequently entrusted with senior positions. In the 14th century, Kraków was one of the most important centres of the trade in Poland. As well as the Basilica of St. Mary, beautiful stained-glass windows from the period can be found at the Church of Corpus Christi in Kazimierz. 13th and 14th-century windows from the Dominican church and monastery are deposited at the National Museum as a permanent element of the Arts and Crafts Gallery.

As we admire Kraków’s Gothic churches, let’s remember the images painted with light and colour, left for us by their mediaeval creators! (Dorota Dziunikowska, “Karnet” magazine)

This text us based on the catalogue for the exhibition The Miracle of Light. Mediaeval Stained-Glass Windows in Poland, edited by Dr. Dobrosława Horzela, National Museum in Kraków, 2020.