Of this can be no doubt: Kraków’s culture has always been able to integrate the most important trends in the arts, architecture, theatre and music.

Author: Bożena Gierat-Bieroń

In early 2024, we find ourselves asking the following question: now that 20 years have passed since Poland’s accession to the EU, have Cracovian cultural institutions, universities and non-governmental organisations made the most of this new “window” onto the world and developed fresh mechanisms of intercultural communication?

They have certainly had plenty of opportunities. The concept of “Europeanisation” of Kraków, initiated by local authorities in the late 20th century (many years before Poland joined the EU), resulted first in the city hosting the European Month of Culture (1992), and in 2000, Kraków was awarded the title of European City of Culture. Kraków joined the select network of European Cities of Culture alongside Avignon, Bergen, Bologna, Brussels, Helsinki, Prague, Reykjavík and Santiago de Compostela. The city benefited from further EU funding and framework programmes including Kaleidoscope, Culture 2000, Culture 2007–2013 and regional funds. Being able to access innovative EU support helped shape modern, forward-looking cultural circles in Kraków, highly skilled at making the most of Europe’s networks.

Let us analyse Kraków’s latest activities by looking at the recently completed EU “Creative Europe” programme (2014–2020). The 13 participating bodies included public institutions on the national and municipal levels and NGOs: Academy of Music in Kraków, Bunkier Sztuki, Cracovian Music Scene Foundation, Krakow Festival Office (KBF), International Cultural Centre, Museum of Municipal Engineering (now Museum of Engineering and Technology), Nowa Huta Cultural Centre, “Rotunda” Association, Ludowy Theatre, Łaźnia Nowa Theatre, Society of Lovers of Kraków’s History and Monuments, Jagiellonian University and the “Multikultura” Union of Associations. Some of the organisations were in charge of several projects, for example the International Cultural Centre oversaw three and KBF five. The artistic dimensions of the projects, acclaimed by international juries, is one of the many answers to the question “What has the EU done for Kraków’s culture?”

Discourse of remembrance and the past

Our EU membership has certainly brought reflection over our cultural identity and included Kraków in the discourse of remembrance. The project Trauma & Revival, run by Bunkier Sztuki between 2015 and 2018, resulted in the presentation of works by Polish artists at the exhibition Facing the Future: Art in Europe 1945-1968 prepared by the BOZAR Centre for Fine Arts in Brussels, also presented at the Centre for Art and Media in Karlsruhe and the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow. Kraków’s instalment of the project was the exhibition Orient showcasing works by artists from Central and Eastern Europe. In 2019, the International Cultural Centre prepared the narrative for the exhibition Years of Disarray. Art of the Avant-Garde in Central Europe 1908–1928. Questions of identity were analysed in European Identities in the Wake of the Crisis published by the Jagiellonian University in 2015, financed as part of the “Literary translations” category. The topic of endangered monuments was taken up by the Europa Nostra network as part of the project Mainstreaming Heritage (2014–2015; Poland’s operator: Society of Lovers of Kraków’s History and Monuments). It’s worth noting that the International Cultural Centre was the Polish coordinator of the celebrations of the European Year of Cultural Heritage (2018).

Renewable cultural energy

The “Creative Europe” programme helped Kraków bolster its presence in European music and dance circles by absorbing state-of-the-art technologies and meeting the EU’s sustainable development requirements. This is shown through the international project Sounds of Changes, run in Poland by the Museum of Municipal Engineering between 2017 and 2019; it was assessed highly by EU experts, placed sixth out of 66 shortlisted projects. The aim was to popularise the concept of shifts within our familiar soundscapes. In 2019, the museum presented the exhibition Phantom Trams by Marcin Dymiter – an audiovisual installation based on field recordings of historic stock of Kraków’s trams. The Hub for the Exchange of Music Innovation (HEMI) project, run by KBF in collaboration with the Kraków Music Scene Foundation between 2020 and 2024, was another great success. It aims to promote the potential of artists from Central and South Eastern Europe representing all genres of contemporary music by providing education in competitiveness and negotiation skills and preparing artist to appear at leading music festivals. The project proposed the creation of a virtual database holding information about the music industry throughout Europe. It was managed in a manner similar to the iCoDaCo (International Contemporary Dance Collective) project, led by the Kraków Choreography Centre at the Nowa Huta Cultural Centre between 2018 and 2020. By promoting myriad forms of contemporary dance, it was implemented by working on individual performances, workshops and meetings with local communities, with a focus on ecological values, recycling and democratic decision-making. The managers of iCoDaCo believe that one of the important values of contemporary performative projects is renewable spectacles and performances, bringing down costs of production and transport. Finally, the latest project of the Kraków Dance Theatre, Beyond Front, is held as part of the latest instalment of “Creative Europe 2020–2027” in collaboration with Cricoteka.

Uncovering potential

The estimation of Polish literature has noticeably increased in recent years, in part thanks to the activities of the Krakow Festival Office. This is bolstered by Kraków’s title of UNESCO City of Literature, our relationships with the European chapter of PEN International and the Versopolis network, as well as EU support. KBF has so far led two literary projects as part of the “Creative Europe” programme: Engage (Young Producers. Building Bridges to a Freer World, 2017–2019) and CELA (Connecting Emerging Literary Artists, 2019–2023). Engage encouraged talented artists to uncover their potential and give them opportunities to produce their own events by providing them with a know-how in managing their own careers. Educators stressed the importance of freedom of speech at a time when hate speech is so prevalent. The CELA project involved over 150 authors and translators, and included a series of activities promoting writing, reading and translation, in particular in less-well-known European languages. The timetable included translation workshops, a festival tour and meetings with publishers.

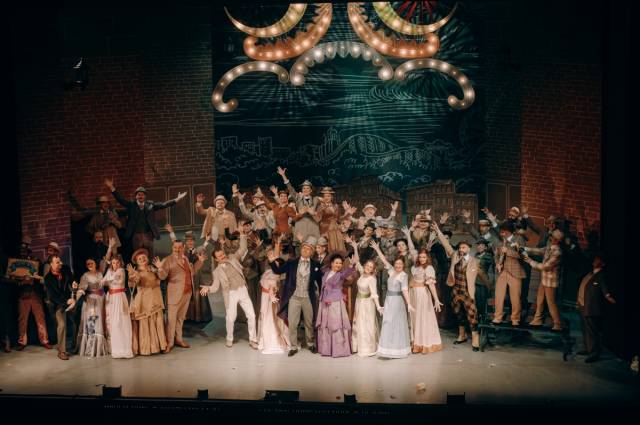

Experiments with texts were also an element of working on storytelling, as part of the PLAYON! performative project implemented by the Ludowy Theatre alongside eight other theatres from all over Europe (2019–2023). The outcome was three spectacles prepared by each institution – a total of 27 variants of classical narratives in interactive formats, using digital technologies and immersion straight from video games. The Łaźnia Nowa Theatre invited artists from abroad to tell stories about cities through performative techniques; the project How Do We Want to Live in the Future? (2014) was an element of the Second Cities – Performing Cities undertaking by a network of European theatres. Guides into inclusive educational practices and training workshops were offered by initiatives including the Małopolska Institute of Culture and Cricoteka (as part of the Erasmus+ programme) and the Academy of Music in Kraków (“Creative Europe”, Score, 2014–2017). The latter was based on an extensive network, and its aim was to bolster collaboration among institutions belonging to the European Association of Conservatories (AEC).

***

International collaboration between artists and creators has made major strides in the development of Kraków’s culture over the last two decades. EU support has helped artists and organisers enter the European market, position themselves in an international context, supported learning of foreign languages and bolstered self-confidence. Artists learn to manage diversity in egalitarian, sustainable ways. EU finance helps release creative energy to support dance theatre in Kraków, and consolidate the music sector and promotional mechanisms of literature, bookselling and reading. KBF, the Museum of Engineering and Technology and Bunkier Sztuki developed the broadest partnerships as part of the “Creative Europe” programme. Networking projects of the International Cultural Centre and the Academy of Music in Kraków have confirmed the international status of both institutions. Statistically speaking, Kraków’s most frequent collaborators are in Germany, France, Sweden and Italy, and, in the second order, in Czechia, Romania, Austria, Estonia and the Netherlands. While ambitious, the relatively new partnerships with Greece, Serbia and Malta are currently one-off.

Article published in 1/2024 issue of Kraków Culture quarterly.

Bożena Gierat-Bieroń

photo by Katarzyna Niżegorodcew

Adiunkt, profesor Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. Jej zainteresowania badawcze dotyczą takich obszarów naukowych jak: polityki kulturalne, polityka kulturalna Unii Europejskiej, dziedzictwo kulturowe Europy, relacje zewnętrzne UE w dziedzinie kultury, dyplomacja kulturalna. Obecnie kierownik studiów podyplomowych Dyplomacja Kulturalna UJ.

Associate Professor and lecturer at the Jagiellonian University. Her main research interests are in the EU’s cultural policy, European cultural heritage, external cultural relations and European integration processes in cultural dimensions. She is currently the head of the “Cultural diplomacy” postgraduate course at the Jagiellonian University.