Did you know that in the 17th and 18th centuries, Carnival coincided with the most popular part of the operatic season of the year?

The timing of the Opera Rara Festival, held in the beginning of the year (in 2021, from 1 February), recalls this Baroque legacy. The history of opera abounds with stories, tales, anecdotes, facts and factoids. Here is a random and totally subjective selection!

Arias

Arias are a vocal and instrumental form with the voice carrying the cantilena, written as a self-contained whole – but this description doesn’t do any real justice to the powerful emotions evoked by arias. While they are being sung, the action is halted so that the protagonist can express their despair, joy, fury, love, triumph, hate… Just listen to the passion and intensity of operatic hits such as Nessun dorma (Turandot), Figaro’s cavatina (The Barber of Seville), La donna è mobile (Rigoletto), the habanera (Carmen), Musetta’s waltz (La bohème), Casta diva (Norma) or the aria by the Queen of the Night (The Magic Flute).

At times passion came from real life rather than the libretto. During her first visit to London, the headstrong Italian soprano Francesca Cuzzoni initially refused to sing an aria because Handel hadn’t written it especially for her. In his frustration, the composer took her up by the waist and threatened to fling her out of the window. Handel’s reputation was to be reckoned with, so Cuzzoni made no more complaints about the part she felt was beneath her just moments before.

Audiences

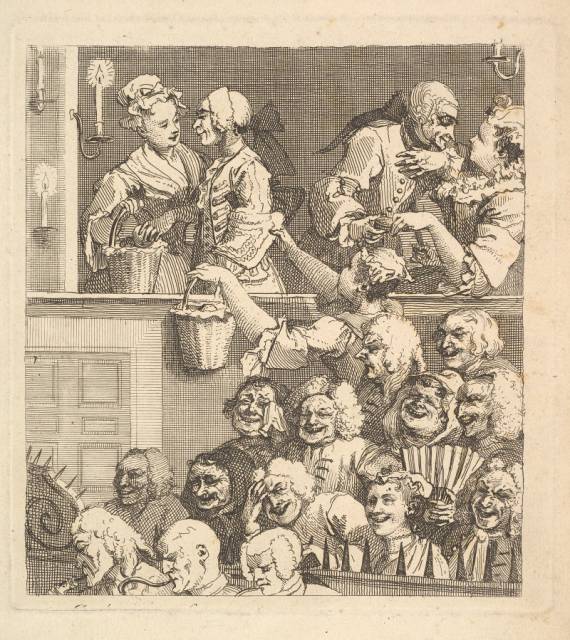

If we went back in time to the days of Handel, Mozart or Rossini, we would be in for quite a shock: going to the opera was seen a great opportunity to meet friends, mingle with high society, win or lose at cards, eat dinner, gossip, flirt… What did composers think of such rowdy behaviour? They didn’t really have a lot of choice. There was little point in putting important arias into the first act since arriving at the theatre on time was seen as tasteless. A ballet section was an essential element of the second act of French operas – no earlier, since that was when the audience partook of dinner. And since guests often needed a short break to get more drinks or powder their fine noses, Italian composers invented the aria di sorbetto with little relevance to the plot and performed by a supporting character. Perfect to sneak out for a few moments, safe in the knowledge one doesn’t miss anything important. Outrageous yet so practical!

The Laughing Audience, etching, William Hogarth, 1733

Brava

Operatic etiquette permits the public to express their enthusiasm during the performance by applauding favourite arias or passages. The custom was frowned upon by Richard Wagner who took himself and his work extremely seriously. At the festival in Bayreuth in 1882, wanting the premiere of his Parsifal to be grand and dignified, he warned the audience that he did not wish his work to be interrupted by clapping. The disorientated listeners held back from applauding throughout the spectacle – and, just to be on the safe side, at the end. Trying to manipulate the audience came back to haunt Wagner: when, during later performances, he called out for appreciation by shouting “Brava!” at the end of the second act, he was silenced by outraged hissing from the audience.

Castratos

The reason for the rise of these “angelic voice” was the papal diktat prohibiting women from singing in church. In the 17th and 18th centuries, castratos also dominated opera stages, enchanting audiences with voices on the alto and soprano register delivered with manly power. The finest – Senesino, Carestini, Caffarelli, Farinelli – revelled in fame and praise. Handel wrote myriad parts for castratos, giving them virtuoso roles as mythical and historic heroes or passionate lovers – from Rinaldo, which launched the composer’s great career in England, to one of his last operas Serse.

By the mid-18th century, public opinion denounced castration as barbaric, and it was finally outlawed a century later. But it didn’t mean the practice disappeared – it was simply carefully hidden. Known as the “angel of Rome” for his performances at the Sistine Chapel, the last known castrato Alessandro Moreschi died in 1922.

Farinelli with his friends, painting by Jacopo Amigoni, ca. 1750

Choir

Choral parts are rarely as popular as arias, but occasionally the choir is given a masterpiece such as Va, pensiero, composed by Giuseppe Verdi for his Nabucco. The chorus of the Jewish slaves in Babylonian captivity, expressing their yearning for home, is one of the most widely known operatic melodies of all time. It is so popular that it is often performed twice during spectacles. At Verdi’s funeral cortege in Milan, almost sixty years after the premiere of Nabucco, the assembled crowds joined voices to sing Va, pensiero.

Death

The mezzo-soprano Kristen Seikaly analysed the plots of 42 popular operas on her blog. Her research reveals that the most common cause of death on stage is murder (52%) followed by suicide (24%) and illness; the latter comes in at just 17% but kills some of the most famous protagonists: Violetta from Traviata and Mimì from La bohème. The most popular weapon is a knife or dagger, used to commit almost 60% of murders including those of Carmen, Nedda from Pagliacci, Lulu, Wozzeck’s wife Marie and Baron Scarpia, Tosca’s arch-villain.

There are times when the operatic death seems to go on… and on… and on… The hero – or, more likely heroine, if we’re honest – has plenty left to say: reflect on her life, bestow her blessings, forgive all that had done her wrong, confess her love, recall her parents, reveal her secrets, cast curses… Such heroines include Violetta and Mimì, Verdi’s titular Aida and Gilda in Puccini’s Rigoletto. It’s no easy life (or death) being an operatic heroine!

Figaro

He first came to life in a series of plays by Pierre Beaumarchais. The dramatist penned a cycle of three comedies centred on the exploits of the cunning valet to Count Almaviva, all three of which have been used as a basis for a total of at least eight operas. The operatic versions have far overshadowed the original dramas, and include Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro and Rossini’s The Barber of Seville. Opera never disappoints!

Flops

What do Traviata, Carmen, Madama Butterfly, and The Barber of Seville have in common? You might think the answer is easy – operatic canon, some of the greatest hits of the genre, some of the most popular spectacles… In its summary of the 2018/2019 season, Operabase’s ranking of the most frequently performed operas placed them in first, fourth, sixth and seventh place, respectively.

But there’s something else: the premieres of all four works were spectacular flops. The audience of Traviata believed that Verdi’s chosen prima donna was far too old (at 38!) to play Violetta. Carmen’s composer Bizet came under fire for the low standing and defective morality of most of the characters, and the critic Ernest Newman wrote that the audience of the sentimentalist Opéra-Comique was “shocked by the drastic realism of the action”. Puccini blamed the poor reception of Madama Butterfly on vengeful critics. Rossini’s The Barber of Seville met a similar fate: many of the audience at the premiere were fans of the composer’s rival who had already written an opera of the same title. It seems that a flop can be the beginning of a beautiful career!

Kraków Opera, G. Verdi, Traviata, photo by Jan Zych

Stay tuned! The second part of the operatic A-Z to be published on 8 February.